Designing Message Queues from First Principles

A layered exploration of ownership, failure, and why queues look the way they do

It’s a new year, and I want to slow down and look at something most of us use without really thinking about: message queues.

We often learn these systems from the outside; from the APIs, configuration flags, and operational guides. But that approach hides the more interesting question: what assumptions do these systems make about failure, ownership, and time?

In this series, I’ll build systems from first principles, one layer at a time. Each layer introduces a constraint that breaks our previous design, forcing us to rethink how systems actually work and evolve.

This is not a comprehensive guide to any particular implementation. I don’t claim to cover every nuance or optimization. The intent is actually simpler: to reason about the core mechanics that make these systems possible, and the tradeoffs that follow from them.

And, hopefully, by the end of it, we will have a pretty good understanding of WHY message queues are designed this way, and HOW they work.

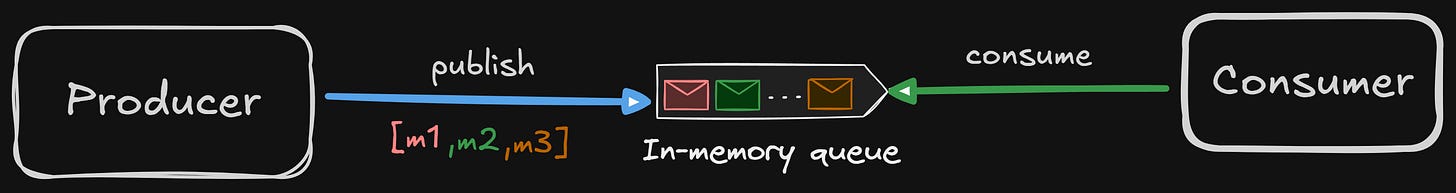

Layer 0 - The Toy Message Queue

Let’s design a toy message queue. And these will be the absolute basic requirements -

The message must exist, regardless of its meaning

A place that stores the message, which can be in-memory, disk, or log, and this is the queue

A way to take out the messages. Consumers ask for the message, and the broker decides which message needs to be sent to that consumer

We will define the smallest and simplest system that can still be called a “message queue”.

Actors

Producers – put messages in

Consumers – take messages out

Queue – holds the messages

That’s it.

Data Structure

It will literally be just an ordered FIFO, a literal queue.

Queue – [m1, m2, m3, m4]There will only be 2 operations.

Enqueue (publish): Producer.append(message)

Queue becomes –

[m1, m2, m3, m4, m5]It doesn’t return anything; it’s fire and forget.

Dequeue (consume):

Consumers.pop_front()Queue becomes –

[m2, m3, m4, m5]

And a critical assumption in Layer 0 is that – “Once a message is handed to the consumer, the system assumes it is done.”

There are no retries, no tracking.

What guarantees does this layer provide?

What if the consumer crashes after popping?

The message is lost

What if the producer crashes after enqueue?

Doesn’t matter; the message is in the queue (obviously, this producer can’t enqueue any more messages since it crashed)

What if the process running the queue crashes?

Well, we lose everything.

What about the ordering of messages?

FIFO ordering. Messages are dequeued in the order they were enqueued.

Right now, the act of dequeuing destroys the information. The system has no idea –

Who took the message

whether it was processed

whether it should be retried

So, on this note, we are done with Layer 0.

Let’s break this design into layer 1 by introducing just 1 problem.

Layer 1 - What if the consumer dies?

Yes, we introduce our 1st failure – “A consumer can die after receiving a message.”

We still have just 1 producer, 1 consumer, 1 queue, but the consumer can crash.

Let’s recall why Layer 0 won’t work here.

Queue - [m1, m2, m3, m4]

consumer.pop_front() <- m1

Queue - [m2,m3,m4]Now –

Consumer pops m1

Consumer crashesWhere is m1?

Its not in the queue

Its not processed (we don’t know it for sure)

Its not tracked

So, it vanished.

This introduces a NEED to track the messages, or you can say, track the states of these messages.

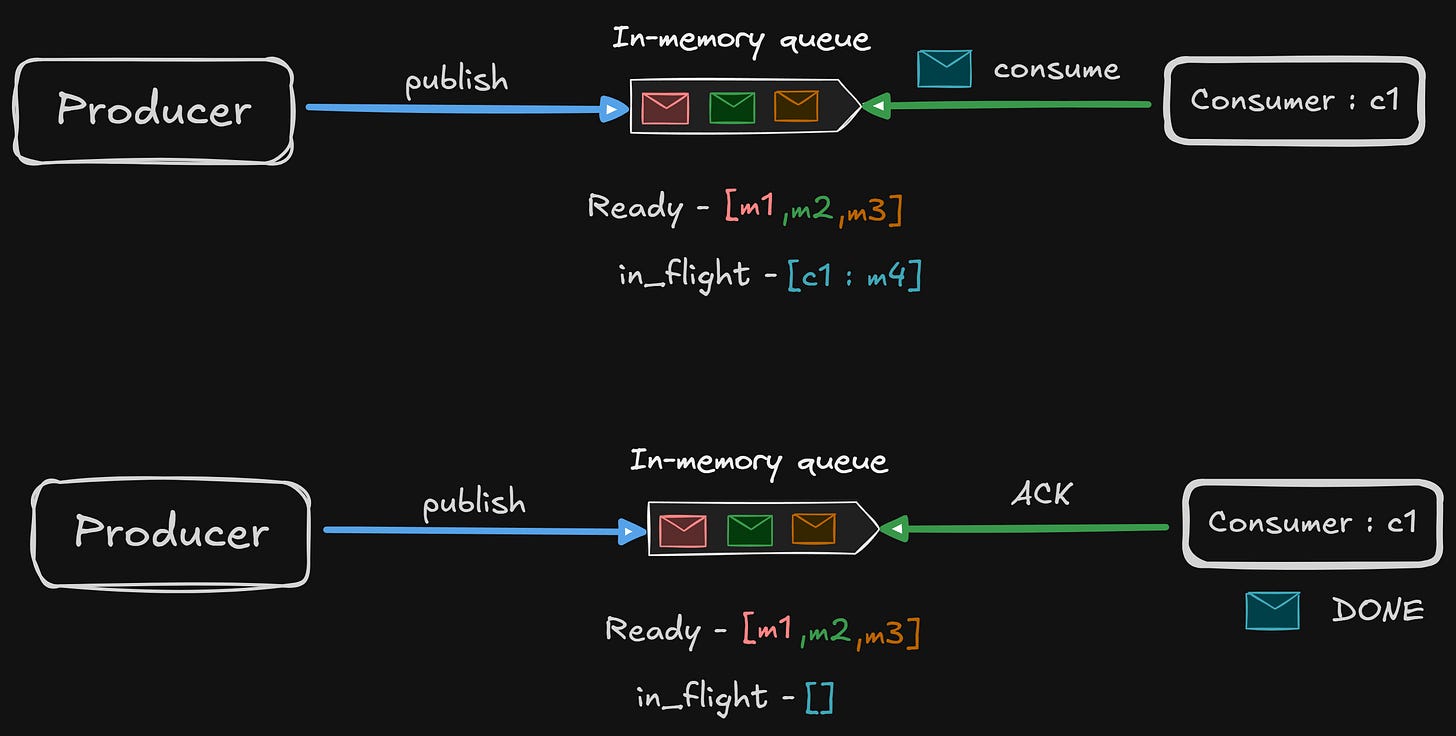

The Birth of ACKs

We need some way to get a message from the consumer about the state of the message.

This is the reason why ACK exists in message queues. We are saying this, every message has a lifecycle –

READY -> IN-FLIGHT -> DONELayer 0 only had:

READY -> DONE (implicitly)New Responsibility of the queue in Layer 1

The queue now must –

Remember which message was handed out

remember to whom

decide what to do if the consumer disappears

This is no longer just a dumb list.

The Simplest Model

The message flows like this –

Queue hands the message to the consumer

Message moves to in-flight

Consumer processes the message

Consumer explicitly says: ACK

Queue deletes the message

This means that if step 4 never happens, the message is not DONE.

The Data Structure Model

We need 2 structures now –

ready queue – [m2,m3]

in_flight messages - {consumer_id : m1}Even with 1 consumer, the system MUST track the ownership to ensure correctness.

With this change, our Layer 1 can now handle consumer crashes.

Let’s look at how our message queue behaves now with consumer crashes.

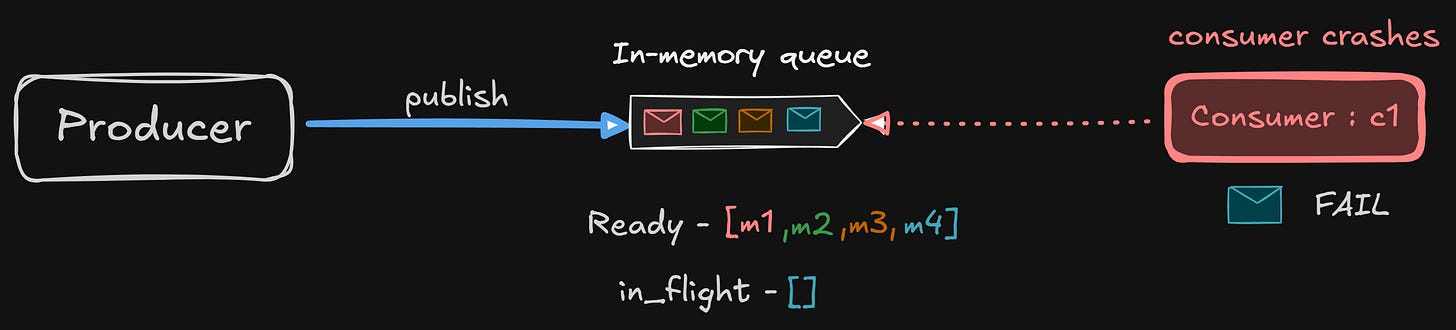

Consumer crashes before ACKs

Queue sees:

in_flight = { c1: m4 }But no ACK ever arrives.

So the queue must:

detect consumer death

move m1 back to ready

ready = [m4, m1, m2, m3]This is a re-delivery.

If m4 failed to get processed, where is m4 enqueued?

Is it enqueued to the front, or to the back of the queue?

That’s one of the major design considerations, depending on how we want our message queue to behave.

Let’s look at a few options.

Option 1: Requeue to the front

Let’s requeue m4 to the front of the queue.

ready = [m4, m1, m2, m3]This makes sense at first because m4 was the earlier work, so it should be retried immediately.

Pros:

Preserves logical enqueue order

Faster recovery from transient failures

Cons:

Poison messages can stall the entire queue

One bad message can dominate retries and cause head-of-line blocking

Option 2: Requeue to the back

ready = [m1, m2, m3, m4]This considers that failed messages should not block others from getting processed.

Pros:

Avoids starvation of other messages

Better throughput

Cons:

Violates strict FIFO

Retries may be delayed indefinitely under load

Latency for failed messages increases

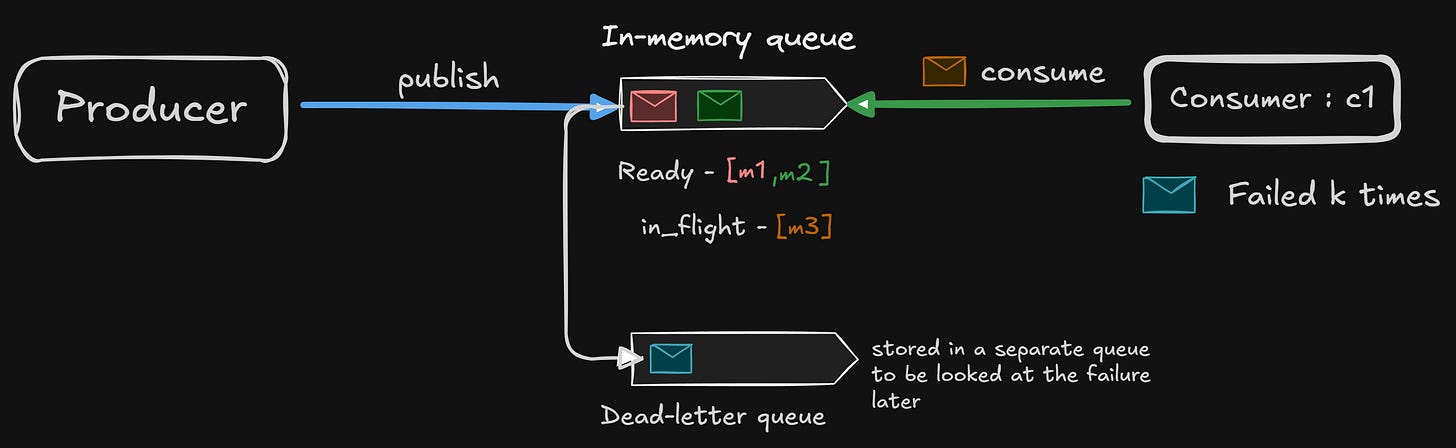

But there’s another option that real-world queues use.

Option 3: Requeue to a different place

Most real queues don’t just enqueue in front or at the back.

They do things like:

Put failed messages in front, but after N retries, put the failed message in the dead-letter queue

back, but with priority downgrade (making sure other messages are higher in priority and get processed)

separate retry queue with delay

exponential backoff

This is how queues stop poison messages from killing the system.

This solves our problem of a crashed consumer/failed message, but now, it also raised further issues.

Let’s look at each of the problems it introduced.

1. Duplicate Messages

If the consumer processed m1 but crashed before ACK:

message m1 was still in-flight, which means it gets redelivered

consumer may process it twice

This is not a bug. It’s a consequence. Our queue promises at-least once delivery.

2. What does “consumer crash” actually mean?

There can be multiple reasons for “consume crash” –

TCP disconnect?

timeout?

heartbeat?

process exit?

Failure detection is now part of the queue’s job. Failure detection is necessarily just guessing accurately. The queue never truly knows if a consumer is dead; it only infers.

3. What if the consumer is slow, and not dead?

If we reclaim too early → duplicates rise.

If we wait too long, → stalled queue

This introduces timeouts and visibility windows later.

We realize a critical aspect of message queues in this layer –

Message queues are not about storing messages.

They are about tracking responsibility.

The queue’s real job is:

“Who currently owns this message, and what do I do if they fail?”

Okay, all good till now. We solved 1 problem, but introduced more nuances.

Before moving to the next layer, I want to think about how the consumers send ACKs to the queue.

Solving that problem can potentially solve a lot of other issues.

Consumers sending ACKs

If we look at some widely used message queues (like RabbitMQ), it uses a long-lived consumer connection with the broker. And that’s how it sends ACKs.

But this question came to my mind –

If the broker only wants an ACK, something like “Hey, message X is done”, keeping a long-lived connection looks unnecessary if the broker only needs an ACK; we can do that via grpc/http as well, right?

But an ACK is not just a confirmation; it’s much more than that.

An ACK actually means:

“The consumer who currently owns this message confirms completion, and all messages before it (sometimes) are also safe.”

So an ACK encodes three things:

Who is ACKing

Which message(s) are being ACKed

When this ACK is valid relative to delivery

Those three constraints are where transport suddenly matters.

If we were to “just send ACK via HTTP/gRPC”, it sounds fine at first. We can do something like –

Consumer receives message

Processes it

Sends

POST /ack { message_id }to broker

It introduces some problems –

Ownership: A message is owned by a specific consumer. So, when the broker receives an ACK, it must answer whether the sender is still the legitimate owner of this message.

With a long-lived TCP connection:

ownership = connection

if connection dies → ownership revoked

in-flight messages are reclaimed automatically

With HTTP/gRPC:

requests are stateless, so there is no notion of “this consumer is alive.”

ACK can arrive after the broker already decided the consumer is dead

Liveness detection: The broker still need to check if the consumer is alive or not, otherwise it will keep sending the messages.

With a persistent connection:

TCP connection reset → consumer dead

heartbeat failure → consumer dead

socket disconnected → reclaim in-flight messages

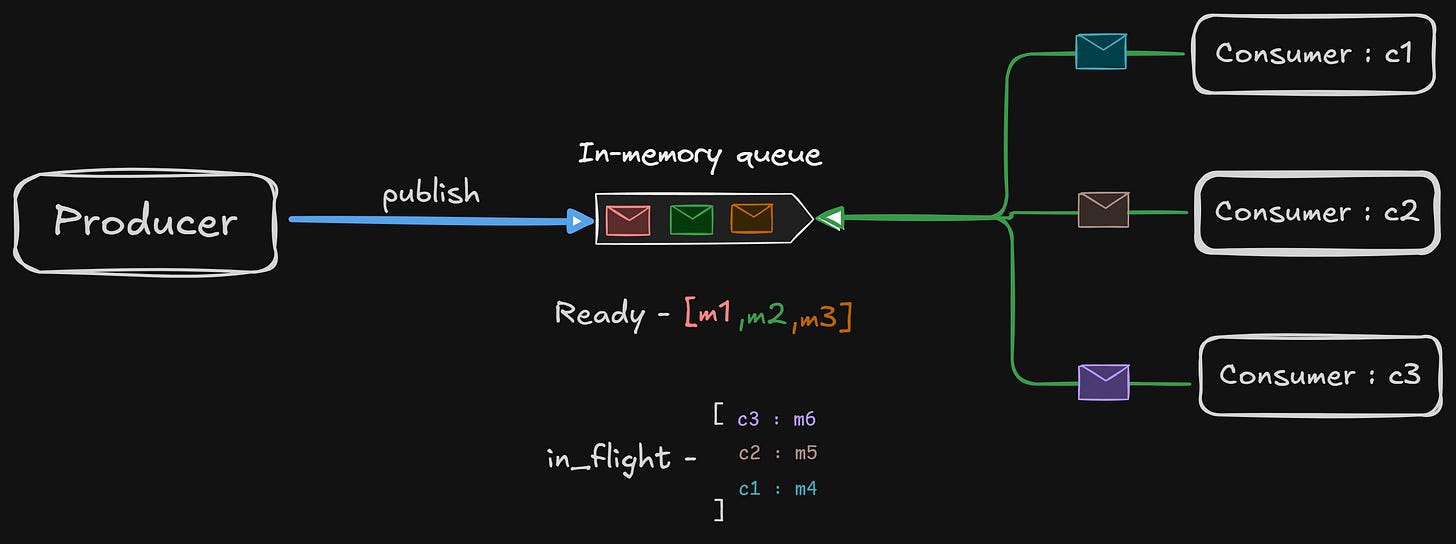

Layer 2 - Multiple Consumers

Till now, we were working with 1 producer, 1 consumer, 1 queue.

But let’s change just 1 assumption: “More than 1 consumer can pull from the same queue.”

Everything else from Layer 1 stays:

messages

ready state

in-flight state

ACKs

re-delivery on failure

With one consumer, life was simple:

one owner at a time, so ordering was mostly trivial

failure recovery was - either the message was processed by the consumer, or it failed

With multiple consumers, the queue must now answer questions it never had to before:

Who gets the next message?

How many messages can one consumer hold?

What does “fair” even mean, to ensure fairness among multiple consumers?

What happens to ordering?

This is where policy enters.

The message lifecycle is still unchanged –

READY -> IN-FLIGHT -> DONEBut now, there are multiple consumers –

in_flight = {

c1: [m6],

c2: [m5],

c3: [m4]

}Ownership is distributed.

Let’s tackle the problem of “who to deliver the message to?”

Delivering Messages among Consumers

Naive Approach: Just give messages to whoever asks

This means –

Consumer calls

deliver()→ this sends an ACK to the brokerQueue pops the next message

Assigns the consumer this message

This raises a few problems.

Fast consumers:

They can take up all the messages

They can build a lot of in-flight sets of messages

Slow consumers:

They will starve

Parallelism won’t be achievable

This will cause head-of-line blocking, just at the consumer level. We need some kind of flow control.

And yes, this is the first appearance of backpressure in message queues.

The queue must limit –

“How many messages can a consumer own at 1 time?”

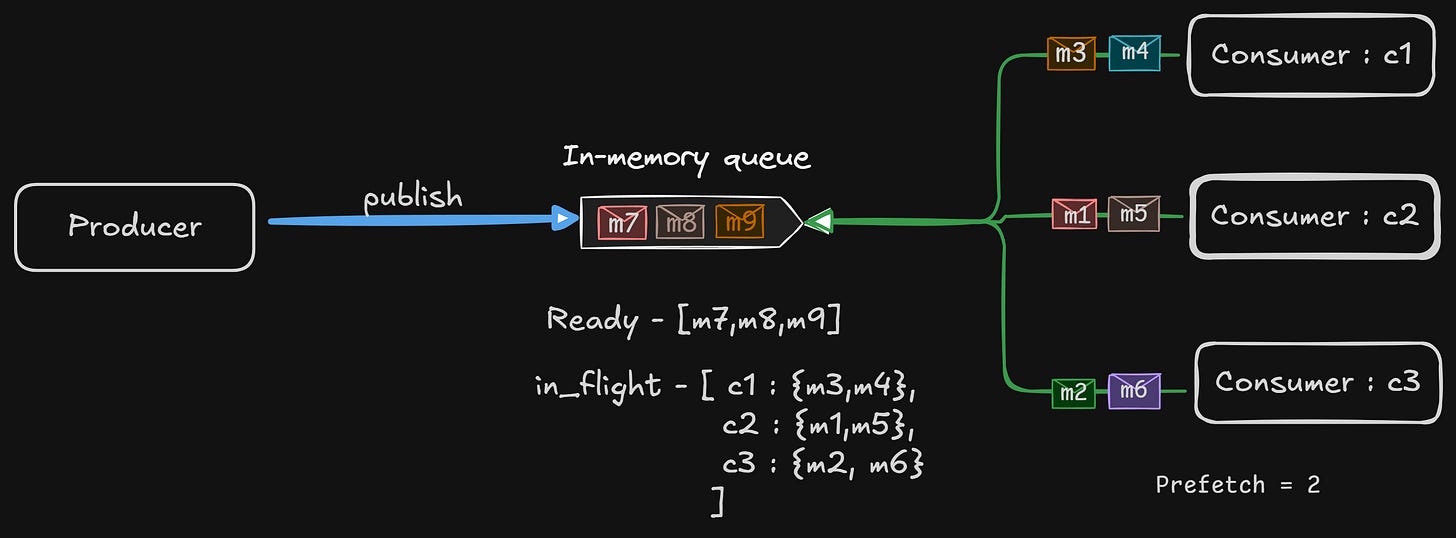

Better Approach: Credit-based (prefetch) delivery

Each consumer has a fixed credit – max_in_flight_per_consumer = N

Rules:

Queue only delivers if the consumer has available credit

ACK frees credit

No ACK → credit remains occupied

This is the fundamental scheduling rule.

It should be noted that RabbitMQ style message queues are mostly push based. When the broker sees that the consumer is ready to take more messages, it pushes those messages.

Ordering Guarantees

The moment we add concurrency, global ordering (within a queue) dies.

For example, let’s imagine – queue - [m1,m2,m3]

c1 gets m1, c2 gets m2

c2 ACKs fast, c1 ACKs slow

Enqueue order doesn’t mean the messages are processed in the same order. And that’s unavoidable.

Queue ordering is still preserved

Processing order is NOT guaranteed

The queue still hands out messages FIFO. Completion happens out of order.

This distinction is critical and often misunderstood.

Failure handling with multiple consumers

Case 1: One consumer crashes

in_flight[c2] = [m2,m5]Consumer c2 dies, broker reclaims the messages.

ready = [m2,m5…]Now, messages may be processed again, possibly by different consumers.

At least once still holds.

Case 2: One slow consumer

Holds messages

Blocks credit

Reduces throughput

The queue must decide whether to wait, timeout, or steal work and give it to others.

This is where visibility timeouts and consumer liveness appear (hold this thought, we will tackle this later).

Fairness

How do we define “fair”:

Do we divide equal messages per consumer?

Do we send the fastest consumer more messages?

Can we use strict round-robin?

Maybe we can use weighted consumers; more weighted consumers get more work?

There is no universally correct answer. It depends on what we prioritize.

Slow Consumers

This is one of the most important pieces to tackle for a broker.

How can we reliably say a consumer is slow, or it’s dead?

The queue can’t know if the consumer is performing a long-running DB transaction, or if it’s about to finish in 2 sec.

It only knows about deliveries, ACKs, heartbeats/connection states.

So, the whole idea of the broker to check for slow consumers is making a good enough inference.

If we wait too long, the throughput collapses

If we reclaim too early, duplicates explode the system

There are a few strategies that different systems use.

Strategy 1: Connection-based liveliness

Rules

Consumer holds a TCP connection, and messages are tied to that connection

As long as the connection is alive, the consumer is considered alive

If the connection dies, all in-flight messages are immediately reclaimed

If the consumer is slow but connected, the queue waits, and credit (prefetch) limits the damage.

So slow consumers hurt themselves and not the whole system (assuming prefetch defined is reasonable).

Strategy 2: Visibility timeout (TTL)

Now let’s look at the alternative.

Rules

Consumer receives message

Message becomes invisible for T seconds

If ACK (delete) happens within T → done

If not → message reappears

This treats slowness and failure the same way.

If T is too short -

message reappears, and another consumer picks it up

original consumer eventually finishes

duplicate processing

If T is too long:

message is stuck behind a slow consumer

throughput drops and retries take forever

So we are forced to guess the average execution time to keep a reasonable timeout.

This model favors availability over precision.

There are numerous nuances to message queues, and many considerations we must take into account to build resilient systems that we use in our everyday lives. It’s practically impossible to cover everything in just 1 post.

So this is where we will stop, before persistence, distribution, and consensus, because the core mechanics of message queues are already fully visible at this point.

Wrapping Up

At this point, we should step back and look at what we actually built.

We started with just a toy queue, a data structure that moved messages from producers to consumers. It worked only as long as we pretended failures didn’t exist.

Introducing consumer failure forced us to separate delivery from completion. Messages could no longer disappear the moment they were handed out. This is where acknowledgements, in-flight state, and redelivery were born.

Adding multiple consumers turned the queue into a scheduler. Fairness, flow control, and backpressure mattered. Ordering stopped being a global guarantee and became a best-effort property.

Throughout all these layers, one thing remained constant: the queue’s real responsibility was never routing or throughput. It was the ownership: tracking who is responsible for a message at any point in time, and reclaiming that responsibility safely when things go wrong.

Once we see message queues through this lens, their design stops feeling complex. The constraints explain the architecture.

A Message

I’ve been thinking a lot about how writers monetize their content in different ways, including paywalls. That’s not what I want for this space.

Everything I write here will stay free; that’s important to me. At the same time, writing takes time, solitude, and energy.

If you have ever felt that my work helped you in some way, and you want to support it, you can do that here —

Articles worth reading

In all my future posts, I will try to mention a few articles that I found interesting, and I feel more people should read them.

The following is an amazing article if someone wants to understand SSTs right down to their implications on how memory is accessed.