Scaling WebSockets: The Complete Guide for Engineers

From the low-level TCP upgrade handshake to Kafka-backed fan-out and distributed session directories

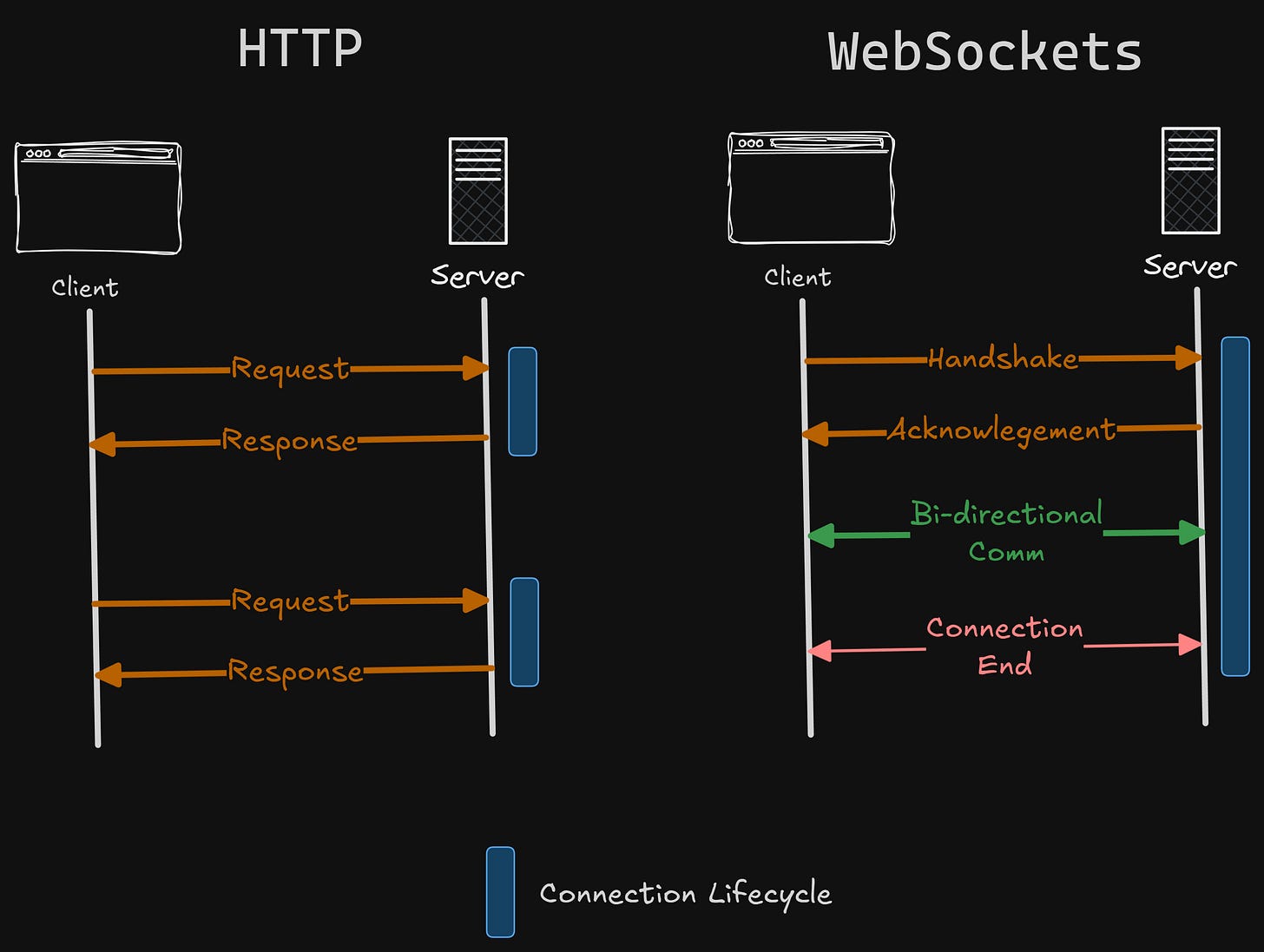

In previous posts, we examined how Webhooks work between servers and how SSE works between a client and server, but it’s only unidirectional.

Websockets are the most primarily used protocol for real-time communication between client/servers. It’s widely used in chat applications, bi-directional communication, and any kind of real-time client-server interaction.

The concept of WebSockets looks simple – both client and server can send each other a stream of text, and well… that’s it, everything works.

But simplicity on the surface hides complexity underneath, and that’s what we are gonna dive into today.

Not just WHAT are websockets, but WHY are they designed this way.

It’s just a long-lived TCP Connection

To understand what WebSockets are, we should know that HTTP is just a protocol that is used for communication across the internet.

And TCP is the way we establish communication between systems.

So, we can imagine something like this –

“When we are talking to someone, the sound is the medium by which we communicate, but we speak a certain language to convey our thoughts. So, sound is like a TCP connection, and the language is HTTP protocol.”

We can talk to someone in Morse code and still be able to understand.

That’s what happens when websocket connection is established.

Client starts with a normal HTTP Request

This is the normal HTTP request sent by the browser to the server, but with special headers.

GET /chat HTTP/1.1

Host: example.com

Upgrade: websocket

Connection: Upgrade

Sec-WebSocket-Key: x3JJHMbDL1EzLkh9GBhXDw==

Sec-WebSocket-Version: 13Key points:

GET request - not POST, not a new protocol.

Upgrade: websocket - this means “let’s stop speaking HTTP after this.”

Sec-WebSocket-Key - random 16-byte base64; used to verify the server understands the WebSocket protocol.

Server checks the headers and replies with a special status

If the server supports WebSocket connections, it replies with –

HTTP/1.1 101 Switching Protocols

Upgrade: websocket

Connection: Upgrade

Sec-WebSocket-Accept: HSmrc0sMlYUkAGmm5OPpG2HaGWk=Once this status line is sent, HTTP ends. There is no body, no HTML, no JSON.

Just a handshake saying — “Cool, let’s stop being HTTP.”

“But what if the endpoint the client is trying to connect to doesn’t support Websockets?”

That’s what the header Sec-Websocket-Accept does.

The magic header: Sec-Websocket-Accept

The server proves it actually speaks WebSockets via this header.

It takes the client’s Sec-Websocket-Key, appends a Globally Unique Identifier (GUID) –

<client_key> + “258EAFA5-E914-47DA-95CA-C5AB0DC85B11”

It does the following -

SHA-1 hash it

base64 encode it

Then reply as

Sec-Websocket-Accept.

If the value matches what the browser expects, the handshake succeeds.

This prevents random HTTP endpoints from accidentally being treated as WebSocket endpoints.

After this point, the connection is no longer just a normal HTTP; the connection follows the WebSocket frame format (out of scope of this article, it’s too complex to explain here).

The Security Concern

Think about TCP, they are nothing but a connection medium, and once it’s established, the client can send anything to a server, as long as it’s via TCP.

Browsers can make WebSocket connections to any server on the internet, even internal services on private IPs (10.x, 192.168.x), even ports we normally can’t reach.

Let’s consider a scenario –

Imagine you are on your corporate network.

You visit a website (http://evilcorp.com/hax.html).

The JS on that website runs –

new WebSocket(”ws://10.0.0.5:6379”);

ws.send(”FLUSHDB”);The browser connected to your internal Redis server (running on 10.0.0.5:6379) and runs the command FLUSHDB.

Redis would execute it.

Your company’s cache cluster was wiped.

From a random webpage visit.

“Yes, in a perfect world, Redis should be under some kind of Auth so that random TCP connections are not acceptable directly. But.. we don’t live in a perfect world.”

We need some way to scramble the plaintext language so that only the server that supports WebSockets can understand it, and others should just ignore it.

And that’s the reason why clients HAVE to mask the WebSocket frames.

Client-side masking forces every frame’s payload to be:

XOR-masked with a random 32-bit key

unpredictable

not a valid plaintext for any legacy protocol

So, instead of the browser sending –

“SET key value”

It sends something like -

XOR(SET key value, 0xA1B2C3D4) --> looks like random binary garbage

No protocol (HTTP/SMTP/Redis/etc.) can interpret that randomness as valid commands.

Scaling WebSockets to Millions

We need to accept the reality that 1 machine has fundamental limits on how much it can hold.

A single machine hits limits:

file descriptors

RAM per connection

CPU per event loop

kernel networking queues

TLS termination overhead

In practice, a strong machine can usually hold 50k–200k stable WS connections comfortably (depending on runtime).

This makes it clear that we want to shard these connections across multiple nodes.

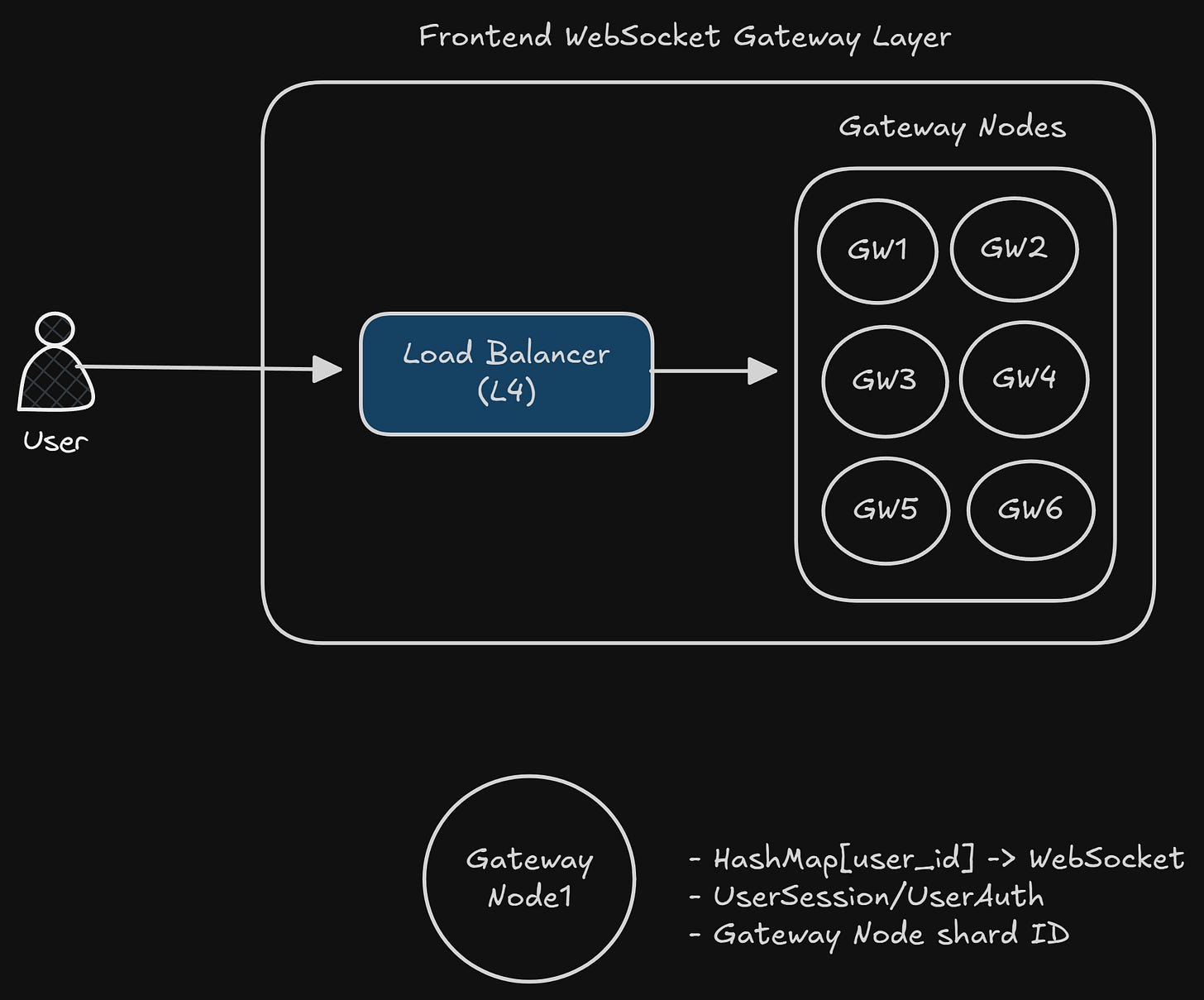

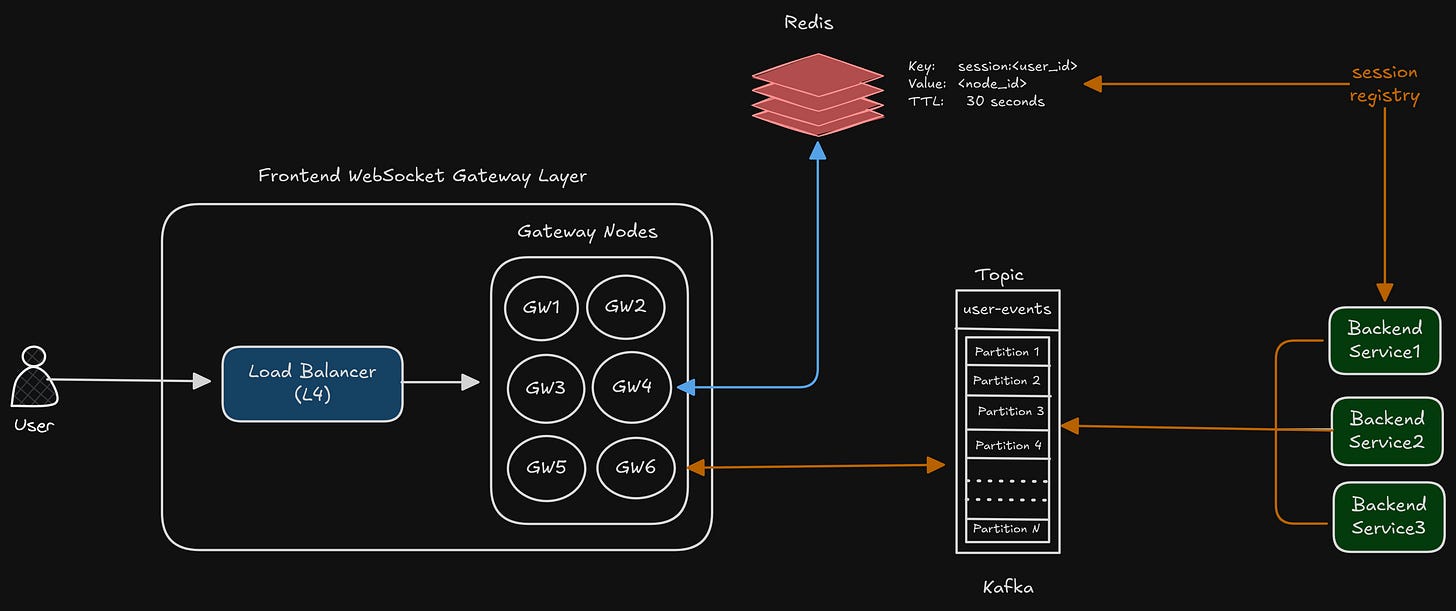

The Frontend Websocket Gateway Layer

This will be the place where all the WebSocket connections will exist. The main goal of this layer would be –

Terminate the WebSocket connections

Maintain the TCP session

Hold the in-memory map: user_id → socket

Receive messages from backend systems and push to clients

Ensure minimal logic per connection

We do NOT put application logic here.

We do NOT talk to databases here.

This layer must be dumb and fast for only one specific thing: to relay messages to clients.

Component 1: Load Balancer

To distribute the WebSocket connections across nodes, we want a load balancer. Since we are working at a huge scale, we want it to be fast, low overhead per connection.

We can use L4 LB. Why?

Because we don’t care about parsing the HTTP or frames, all we care about is forwarding the bytes to the respective servers.

Sticky TCP connections

WebSockets are stateful.

A connection must stay on the same server until it dies.

We would want some stickiness within a long-lived TCP connection.

Stickiness methods:

source IP hashing

consistent hashing

PROXY protocol + our own mapping logic

cookie-based stickiness (at L7, but less preferred)

During its lifetime, all packets of that connection must flow to the same server; otherwise:

the TCP state machine breaks

sequence numbers get messed up

kernel drops packets

the connection is invalid

L4 load balancers don’t understand WebSockets. They only understand TCP.

And TCP absolutely requires that:

A given connection (5-tuple: srcIP, srcPort, dstIP, dstPort, protocol) always maps to the same backend.

We are not maintaining stickiness across sessions, but within a TCP connection, so the bytes are always forwarded to the same backend.

Component 2: WebSocket Gateway Nodes

These will be the servers that actually hold the connections. They should do –

Terminate WebSockets (after Upgrade)

Maintain millions of TCP sockets collectively

Keep a local lookup: user_id → socket_handle

Keep heartbeats/pings alive

Subscribe to a backend pub/sub system (Kafka/NATS/RedisStreams)

Push messages from backend → right socket

As stated above, we don’t want to make DB queries, do any logic, or call dependency services; we want this to be as minimal and fast as possible.

Each of the nodes here holds -

HashMap of sockets

Small metadata (maybe auth/session token)

A shard information (to hold which node it is a part of)

A consumer connection to a message bus (maybe Kafka, we will look at it later)

“Now, if a message needs to be sent to user U123, how do we know which gateway node U123 is connected to?”

That’s the next part of the architecture. Let’s dive in.

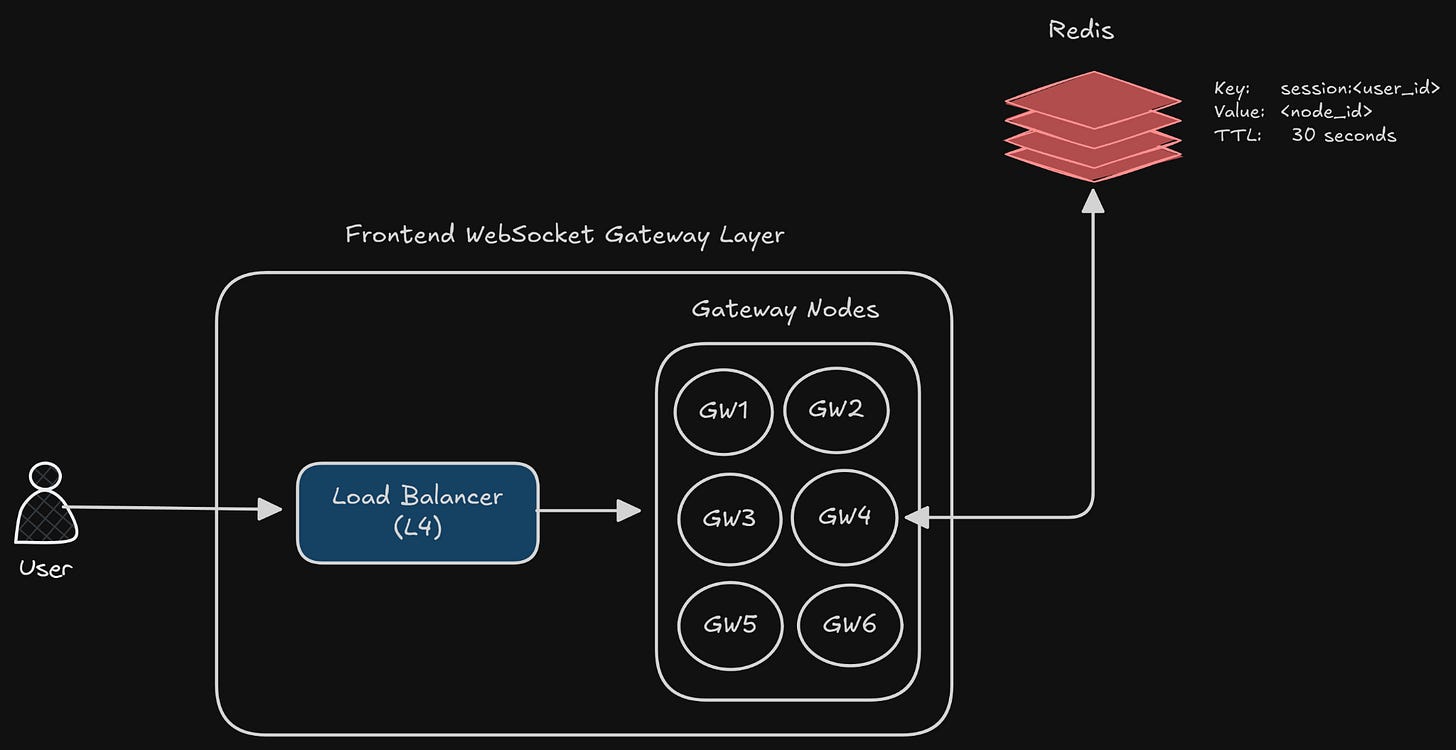

The Distributed Session Directory

As we saw earlier, each node can only contain a few socket connections, so let’s assume –

GW1: holds 70k sockets

GW2: holds 60k sockets

GW3: holds 80k sockets

GW4: holds 90k socketsNow, User123 connects and lands on GW3.

The backend server wants to send this user a message, but the question is, “Where is user123’s socket?”

Our goal for this layer is simple –

“Given a user_id (or session token), how would the backend know which gateway node currently holds the user’s WebSocket connection?”

This is a routing problem, and if we can’t solve it smartly, the whole system fails if we have more than 1 gateway node.

BAD Solution: Broadcast to every gateway node

We say, “I am going to broadcast the message to all gateway nodes; you guys figure out who has the socket and send the message.”

This will melt the CPU at scale; also, it makes the gateway nodes unnecessary application logic (which we agreed not to do).

The network egress explodes, this isn’t a viable option.

GOOD Solution: maintain a centralized mapping

We can store the user_id → gateway_node mapping in the store.

user123 → GW3

user789 → GW1

user456 → GW4This will be the session directory.

How do gateway register users?

When a user authenticates their WebSocket connection, the gateway sends a small write to a shared store:

HSET session:user123 node=GW3 last_seen=timestamp

EXPIRE session:user123 30“Why 30 seconds TTL?”

Because we use a heartbeat model.

The gateway renews the TTL periodically:

every ping/pong cycle

or every N seconds

If a node dies, its entries expire naturally.

What store should we use?

We need a store with –

Very fast reads and writes

TTL support

Small size

I think the most common choice would be Redis (Redis cluster or sharded Redis)

O(1) read/write

built-in TTL

single-threaded = predictable

insanely fast for this workload

What do we store?

We want to store as little data as possible. It can be as simple as –

Key: session:<user_id>

Value: <node_id>

TTL: 30 secondsIf the user disconnects, the old entry expires (due to TTL), or it is overwritten by the new one.

Now, answering the original question –

“How do we know User123’s socket?”

The backend queries Redis - GET session:user123 -> returns GW1.

That’s what we needed.

Once the backend knows that user123 is on GW1, it publishes the message to a shard, or a topic consumed ONLY by GW1.

That’s what we are gonna see next.

Not every gateway should receive every message

Only the right gateway should receive user-specific events

Efficient Message Routing (Fan-in → Fan-out)

Now that we have:

Gateway nodes that hold sockets

A session directory that tells us which node has which user

We need a clean, scalable way to deliver messages to those nodes.

Imagine we have the following –

GW1, GW2, GW3, GW4

And the session directory is –

userA → GW3

userB → GW1

userC → GW4Now a backend service wants to deliver events:

message to userA

message to userB

message to userC

“How does it push each message to the right gateway, without sending it to everyone?”

We need a routing layer in the middle.

Naive approaches

Let’s look at a few options and the reason why they might fail.

Sending an HTTP request directly to the gateway node

It will work for 20k users. But will die at 1M+.

too many TCP connections

gateway node IP changes on autoscale

no batching

high latency under load

Using Redis pub/sub with 1 channel per user

In theory, it can work until a certain point.

Redis pub/sub is not horizontally scalable (although this has changed since Redis 7.0)

millions of channels = memory pressure

Messages dropped under load

We need a proper event bus (with partitions for horizontal scalability).

Shared Message bus with Partitioned Topics

We do the following –

Backend publishes events into a broker instead of to gateway nodes directly.

Gateway nodes subscribe only to the partitions responsible for the users they host.

Message routing scales horizontally because partitions shard the load

For this article, let’s use Kafka as a message bus (there are other better options like NATS, which is more preferred for websockets; it’s super light and simple to operate).

Designing the Topic Structure

We want the messages from backend → gateways to be partitioned in such a way that:

Each partition is consumed by exactly one gateway node

Nodes only receive messages belonging to the users they actually own

Let’s look at how to design it.

Topic: user-events (with multiple partitions)

We can keep the partitioning key as gateway_id (or maybe some hash of it).

So, it will be something like this –

GW1 → partition 12

GW2 → partition 07

GW3 → partition 12Since Kafka guarantees that “all messages for a gateway_id land in the same partition.”

Now, if a user is connected to GW3, their event flows will be something like –

Backend publishes an event for userA -> get the

gateway_idfrom Redis, say GW3GW3 consumes partition 12

GW3 finds the userA’s socket

Writes the message to that socket

This means that –

No other gateway reads that partition 12

No other gateway does any unnecessary work (if the message doesn’t belong to their set of users, they shouldn’t care)

All routing is naturally sharded

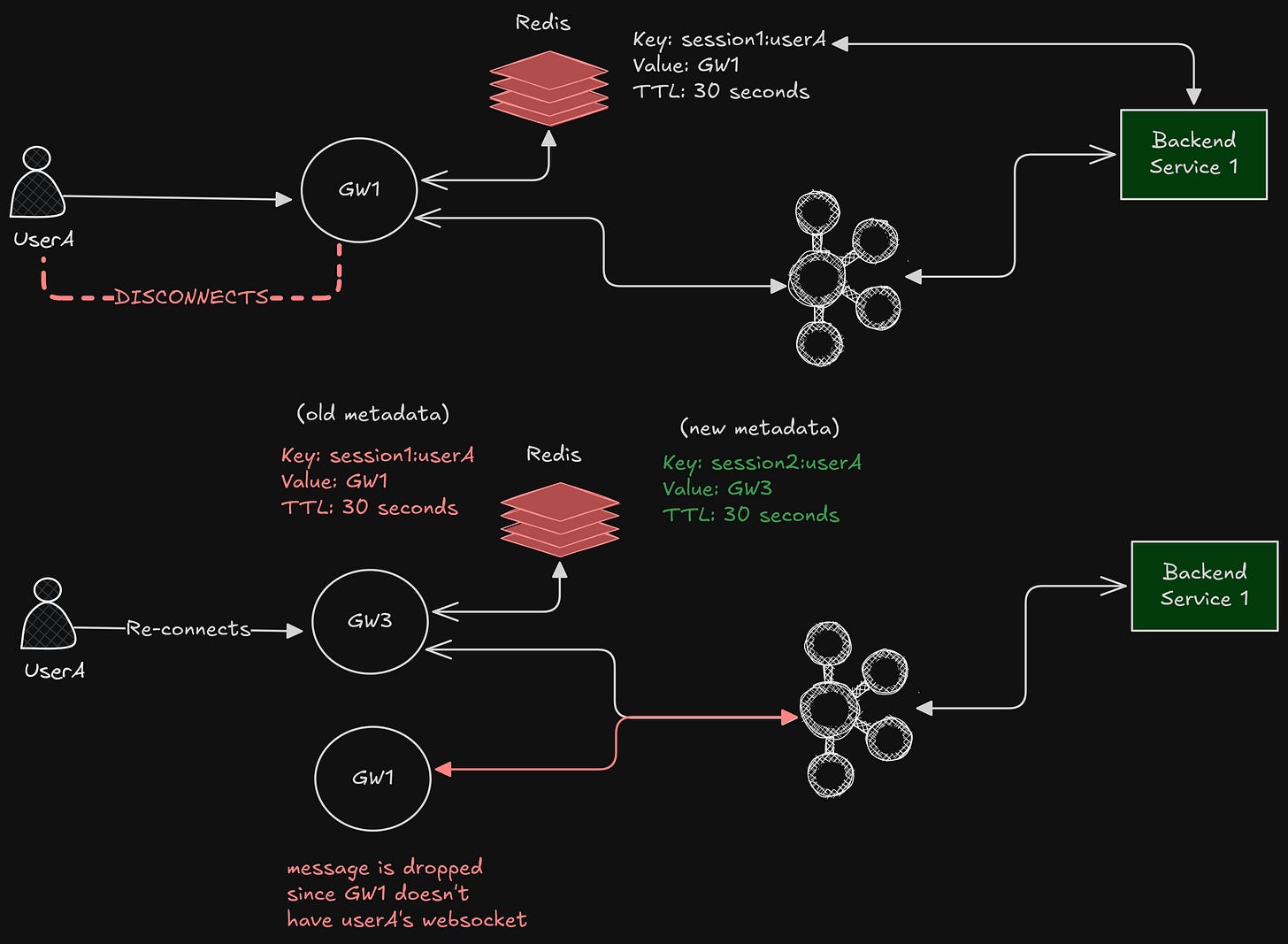

While thinking more about this problem of “what happens if the user disconnects?”, I found some nuances that I think needs to be addressed.

Ordering Guarantees

Imagine a scenario.

Initially, UserA is connected to GW1, which means its messages will be in partition 95

UserA disconnected and connected to GW3, let’s say partition 42

This means that its message might be sent to GW1 even if userA might not be connected to it.

Will this be an issue? Well, not yet.

If GW1 receives the message for UserA, it will check –

“Do I have userA’s socket?”

“Nope”

“Fine, let’s drop this message.”

Why is dropping fine?

Because the system will eventually correct itself when the next heartbeat happens (TTL will refresh in our session directory).

Handling Disconnects

There can be messages that might be dropped as the user might not be connected. We need a way to get those messages when the user reconnects.

When a user reconnects:

they may land on a different gateway

the routing key changes from

old_gateway_id→new_gateway_id

At that point, Kafka ordering across gateways is not preserved, and this is intentional.

Trying to preserve ordering across reconnects at the transport level would require:

pinning users to partitions

forwarding messages between gateways

or dynamically reassigning partitions

All of these introduce tight coupling and failure amplification.

How global ordering is restored

Every message is assigned a monotonically increasing ID (per user or per conversation) and is persisted durably before any real-time push.

The client maintains:

last_seen_message_idOn reconnect, the client requests a sync:

GET /messages?since=last_seen_message_idThe backend responds with all missing messages in order, based on message IDs.

This guarantees that:

messages are eventually delivered in the correct order

gaps caused by disconnects are repaired with sync

duplicates can be safely ignored by ID

So in this way, the system guarantees:

In-order delivery while connected

In-order recovery after reconnect

Eventual consistency across connections

The User Flow

The above architecture feels overwhelming, but let’s look at the flow to understand it better.

“User A sends a message, and the message needs to be sent to User B, C and D.”

Let’s assume the registry as follows –

session:userA → GW2

session:userB → GW1

session:userC → GW4

session:userD → GW3We break the flow into 4 phases.

Phase 1: UserA → Gateway Node

GW2 converts the WS frame to an internal event

UserA is already connected to GW2, so a WebSocket frame comes into GW2.

It contains something like:

{

from: “userA”,

to: [”userB”, “userC”, “userD”],

body: “hello”

}Convert this data into internal protobuf/JSON objects to forward to the backend.

GW2 publishes the event to the backend via Kafka

It was published to the Kafka topic, something like –

client-events

partition = hash(GW2)

payload = message_from_userAThis is fan-IN: all inbound messages go into the backend pipeline via Kafka.

The gateway never talks directly to other gateways.

Phase 2: Backend Auth/Business Logic

Backend consumes the “message from UserA”:

Validates that UserA can send messages

Applies business logic

Figures out the fan-out targets: targets = [userB, userC, userD]

For each target user, the backend must now route messages to the correct gateway node.

Phase 3: Backend → Correct Gateway Node routing

This is where the session registry and partitioned Kafka come into the picture.

Backend does the following –

For each user in [B,C,D]:

Gateway_for_user = Redis.GET(session:userX)Let’s say, we get the following, and the backend splits the outbound messages by node –

userB → GW1 -> [message_for_B]

userC → GW4 -> [message_for_C]

userD → GW3 -> [message_for_D]And it publishes each message to the user-events topic with its partition –

Kafka topic: user-events

Partition = hash(GW1)

Payload = event_to_userBPhase 4: Gateway → WebSocket Delivery

Let’s take GW1 as an example (responsible for UserB):

GW1 consumes its assigned Kafka partitions

Sees a message for userB

Goes to the local map:

userB → socket_fdWrites the WebSocket frame:

WS: “hello”

The same thing happens independently on GW3 (UserD) and GW4 (UserC).

Each gateway only touches its own sockets.

No gateway sends messages to another gateway.

Wrapping Up

At this point, WebSockets stop looking like “a pipe between a client and server,” and start looking like what they really are: a routing problem disguised as a TCP connection.

The moment we scale past one machine, the rules change.

Gateways are dumb because they have to be fast.

The session directory exists because somebody needs to remember where everyone is.

Kafka partitions aren’t an optimisation; they’re the only sane way to fan out messages without burning CPU.

Dropping messages on old nodes isn’t a bug; it’s how the system heals itself.

Real-time systems don’t scale by being clever.

They scale by being predictable.

A clean separation of responsibilities:

connection handling → state tracking → message routing, is the difference between a system that works for 10,000 users and one that can handle a million.

I think what makes systems brilliant is how simple it looks once they’re laid out flat on the paper, but achieving that is a process of trial and error.

We break things, fix things, improve things, and that’s how a system is made.

A Message

I’ve been thinking a lot about how writers monetize their content in different ways, including paywalls. That’s not what I want for this space.

Everything I write here will stay free; that’s important to me. At the same time, writing takes time, solitude, and energy.

If you have ever felt that my work helped you in some way, and you want to support it, you can do that here —

Lets say we want to send message for user b. The backend reads from redis that user b is connected to gateway node 1. But it uses hash of user b as partition key to dispatch the message . How is the information from redis store used here ? Doesn’t

It seem redundant if Kafka is taking care of all routing